You’re reading CX Stories, a newsletter about customer experience innovation. If you want to join the 6000+ lovely people who receive it every month, just click the button below.

This is an announcement for passengers travelling on flight AC877 to Montreal. There will be no toiletsavailable on this plane. I repeat, there will be no toilets available on this plane.

Panic ensured.

People started clambering over each other to get to the bathrooms.

Some made a dash for the pharmacy, looking for absorbent options.

An older woman snatched a bottle of water from her husband’s lips, chastising poor Eric for his fluid-intake stupidity.

A few minutes later, the speaker crackled into life again.

Ladies and gentleman, to clarify my previous messages, the toilets on the plane will be out of service until it has taken off.

The importance of clear communication, eh?

Organisations spend a lot of time trying to design superb customer experiences. They think through the insight, the idea, the way it could be implemented. They get the right systems, people and processes in place. Then the launch to the public, seeing how well it lands.

Sometimes things work, sometimes they don’t. But most annoying is when everything that’s meant to work, works, but customer don’t realise because the communication is so poor.

My favourite example of this is to think about the digital boards in train stations.

If you walk onto a platform and see this sign, you feel instantly relaxed. You get your phone out, scroll through TikTok (well, argumentative Facebook neighbourhood groups for me), and wait for the train the pull up.

Whereas if you see this sign, panic ensues. You worry you’re going to be late home. You presume the whole network may be down. You put your ear to the floor to try and hear if the train is rumbling towards you (just me?).

In reality, most of the time the service is running completely fine in both scenarios. The only thing that’s changed is the communication around it. And it’s that communication – the simplest, cheapest, easiest part to get right – that defines the experience the customer has, the way they feel in that moment.

I’ve had a few examples of this recently.

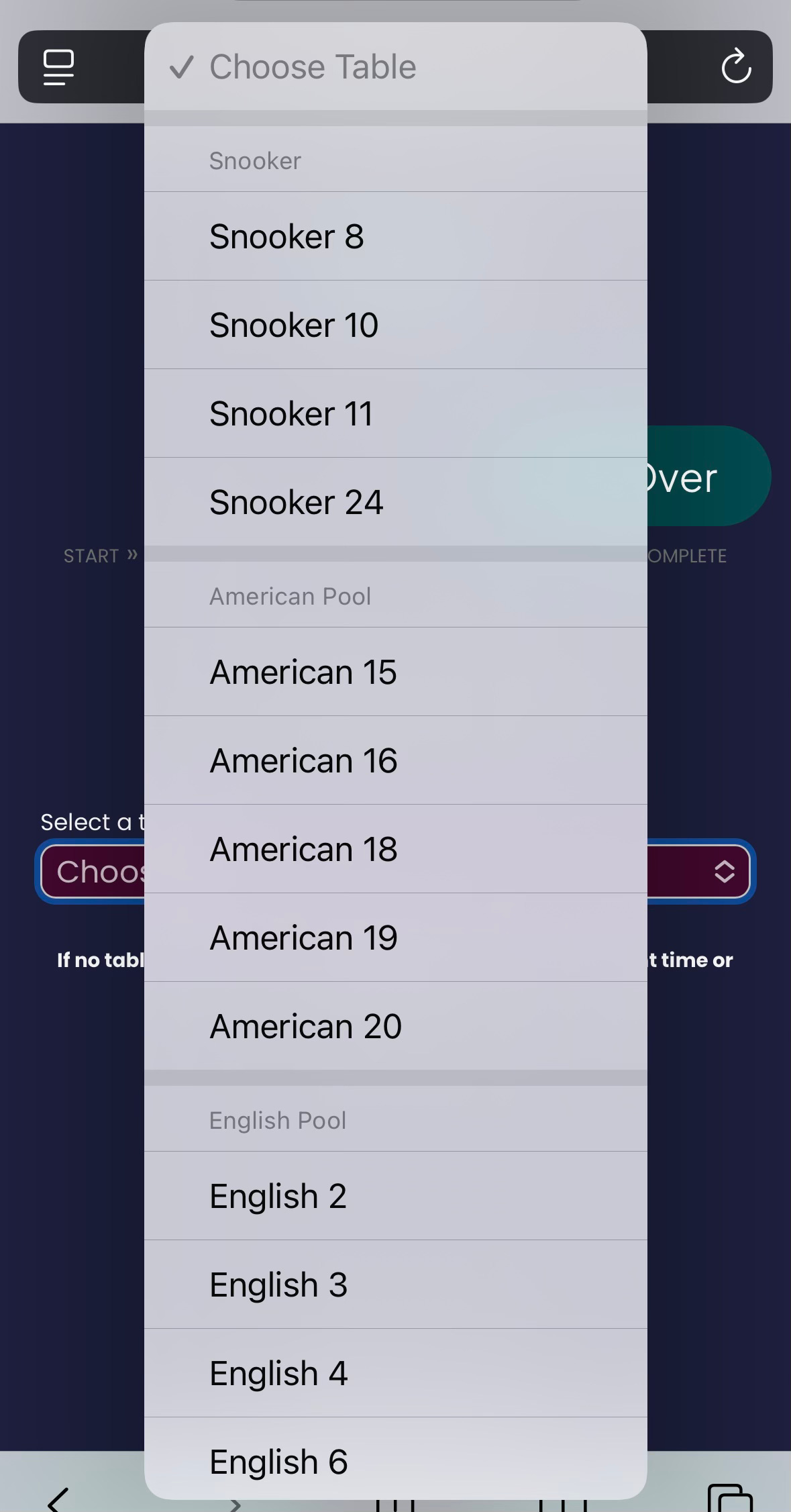

When I went to book a snooker table at a venue I hadn’t been to before, I was greeted with this screen. It took several minutes, and eventually a phone call, to work out these were specific tables numbers. (I also put this on LinkedIn, just to check it wasn’t just me being stupid. Some people thought it was me being stupid. But most agreed they would have been confused).

Another day, I was due to be running a workshop in Newcastle, getting the train up that morning for a 1pm start. At 8am, this notification arrived on my phone and in my inbox. Not the kind of thing you want to see when you’ve only got a few hours to get to the other side of the country.

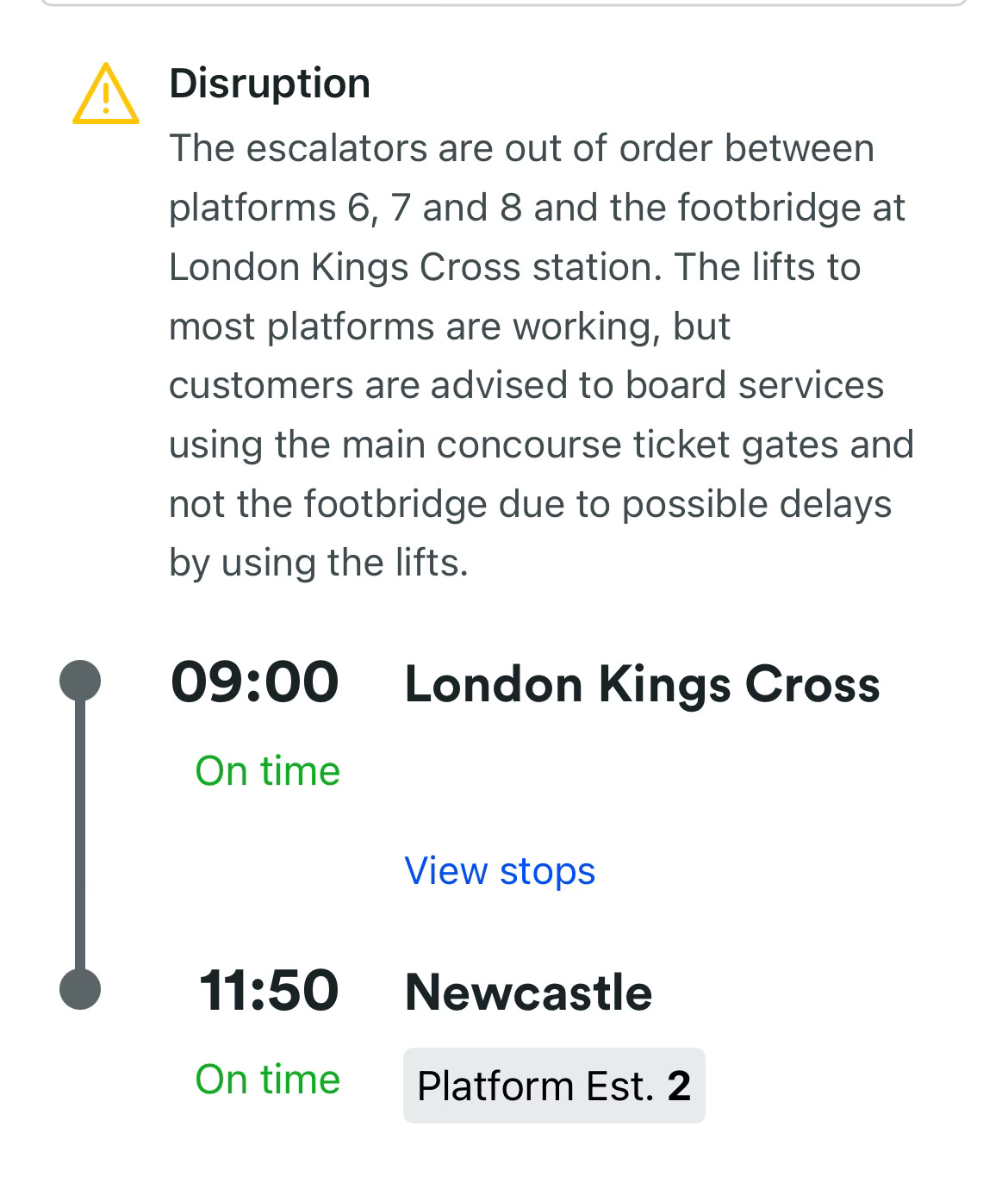

I tentatively clicked the link to find out what the disruption was that was going to affect my journey, and…

(Now, obviously this information matters to some people. But how about we start that email subject line with the words ‘YOUR TRAIN IS ON TIME, BUT…’)

I had another enjoyable one on a plane, too, this time with colleagues not thinking through how their words might land.

As one of the cabin crew walked through to hand out drinks at 36,000 feet, the trolley was causing him some bother.

Oh for god’s sake he half muttered to himself. Absolutely everything is broken on this old plane!

The sea of nervous smiles that greeted him caused a very hasty retraction and an attempt at reassurance.

Organisations need to think through the communication of the experience in as much detail as they do the pricing and the process. And not just for the customer’s benefit, but for their own bottom line, too. Because what do you think happens if people are confused? They get in touch to try and clear things up, taking up colleague time or making costly phone calls.

Doing this well means making sure the communication is there in the first place, and when it is, thinking about the customer who’s receiving it: what they might know already or need to know; the easiest way for them to receive it, not for the company to send it; and how the customer might feel when they receive what is about to be shared.

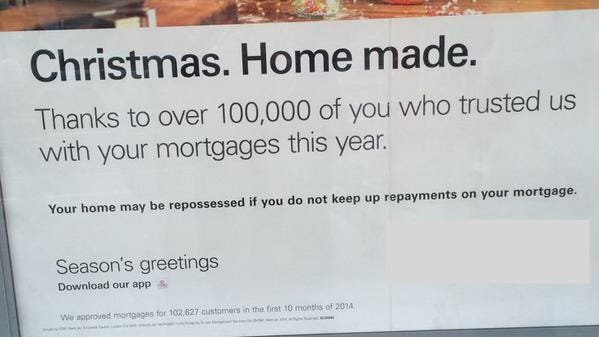

Ten years later, there’s still no better example of when this can go wrong than a Christmas card one of the banks sent to every customer who had taken a mortgage with them that year. It’s a lovely idea, which helped the bank get a lot of publicity on the social media channels of the time, and get to speak to lots of their customers that day.

Merry Christmas. But don’t spend too much on presents, because…

Thanks for reading this article, I really hope you enjoyed it. You can subscribe to my monthly newsletter below, find me in picture form on Instagram @johnjsills, or in work mode at The Foundation and LinkedIn.