You’re reading CX Stories, a newsletter about customer experience innovation. If you want to join the 6000+ lovely people who receive it every month, just click the button below.

So, how are those new year’s resolutions going? This is usually about the time when those good intentions made whilst hanging out at home start to meet the crushing reality of being back at work.

I’m not usually one for resolutions (except for the year I resolved to take up drinking whisky, that one stuck) but this year I have made a fairly significant change – all because of the price of a sandwich.

And I think this sandwich story tells us something about how to make change happen inside a big organisation – because it’s much easier to say you’re going to change a behaviour than it actually is to change it.

Regular readers will know that late last year, my writing-about-places-I-like curse struck again, when my favourite local sandwich shop closed down.

I probably hadn’t realised what a habit it had become to buy my lunch there every day. But with my default option gone, a whole world of food options opened up to me. The new Gail’s down the road? SushiDog, to pretend I’m being healthy? How about Sainsbury’s, for the world’s most confusing meal deal?

With this array of options laid out in front of me, I did what any of you would have done.

I went to the new sandwich shop that took the place of the old one. (Paradox of choice, amirite?)

The people seemed nice enough. The menu, limited, but interesting. Ordering, it was ok, given they were still figuring it out.

But the price? £12. £12! Now at the risk of sounding like a cheapskate, that did take me back. Even for London, that price was punchy. But it was Christmas, I’d already ordered, and I’d pay anything to avoid the social embarrassment of cancelling the order.

And after all, it was a New York-inspired sandwich bar. This could be a sandwich of Joey proportions.

It was not. In fact, it was one of the most disappointing lunches I’ve ever had.

So now, after a decade of sandwiches, I’m going to start bringing my own lunch into work.

But why now? At any point in the last decade, I could have clocked how much money I was wasting, how long I was queueing for, how restricted my choices had been. I’ve even bought fancy lunch boxes, soup containers, and lunch-focused recipe books. But still I went to the shop.

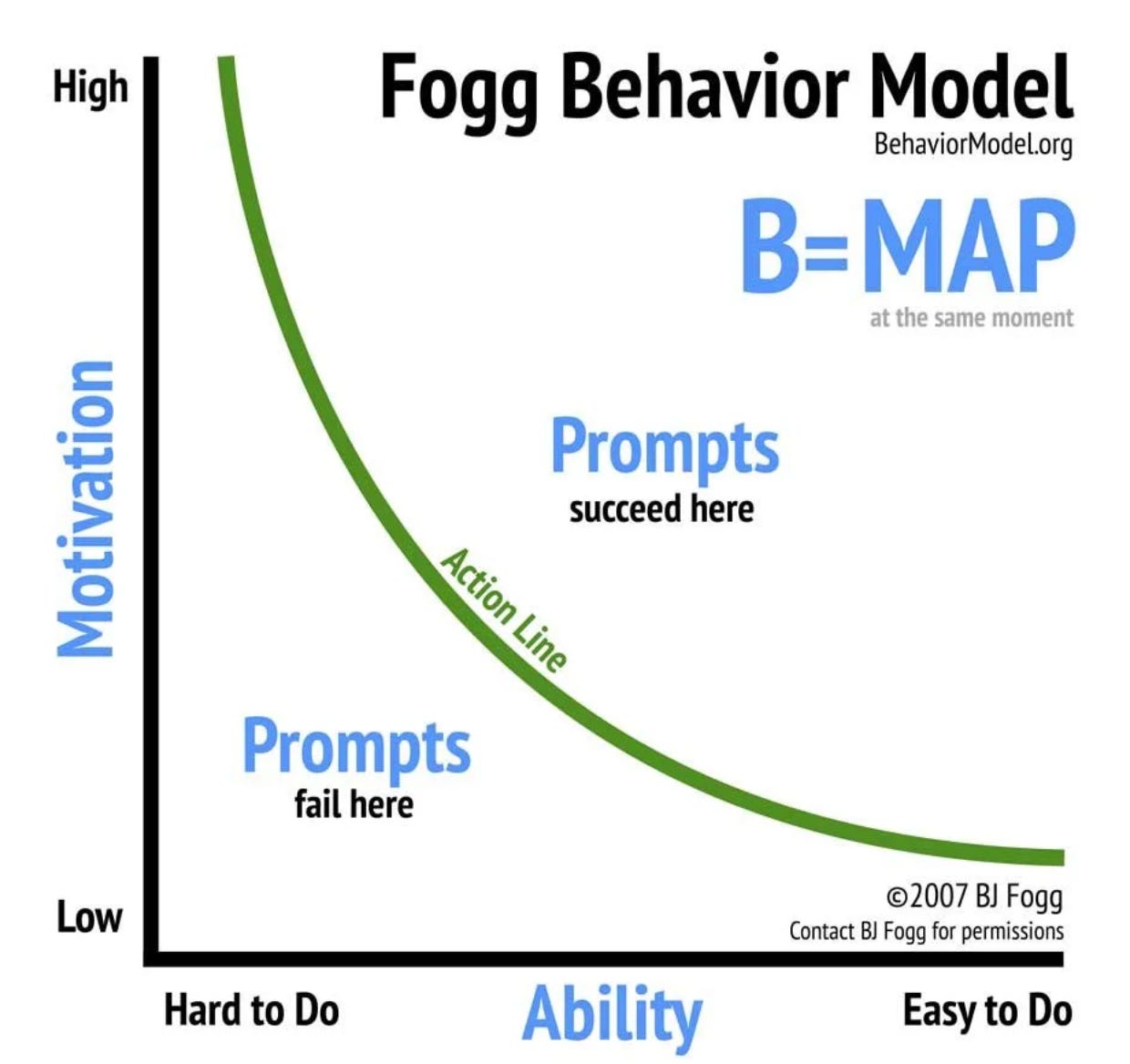

In 2007, the social scientist and author BJ Fogg shared his theory of behaviour change with the world. In it, he argued that for any change in behaviour to occur, three elements must converge at the same time: motivation, ability, and a prompt.

For me, the motivation (wanting a good lunch) was there, but it was much easier for me to go to the shop than make my own, even with the containers and recipe books ready to go at home.

Crucially, I didn’t have the trigger, the prompt to shake me from my sandwich-buying slumber. The way I’d always done things was comfortable and easy. This is the problem most leaders and organisations face when trying to create a better experience for their customers.

They tend to focus on motivation, hosting big events and telling their teams ‘we really care about customers’ and ‘we want you to do the right thing’.

Often isn’t backed up by giving their colleagues the ability to do it. This might mean them not having the right tools and systems, or it could be colleagues not having the autonomy or empowerment to do what’s right for customers.

And if colleagues do have the motivation and ability to make things better for customers, do they have the prompt, the trigger to do it? The change from the old, safe way of working into something bold and new?

For me, my favourite food place closing combined with the astoundingly high price for a cr*ppy lunch was the prompt I needed to shake me from my sandwich slumber. So now, I have the motivation, I have the ability, and I have the moment to shift me into a new behaviour.

As we step into 2026, it’s tempting for leaders to make all sorts of customer-led promises to their colleagues. But if they want real change to happen, they need to be clear on the prompt, the story, the moment that’s going to act like a lightning bolt in the organisation, building belief and creating the change you want to see (something that Charlie Dawson in The Customer Copernicus calls ‘Burningness’).

Without that, this time next year, you might be making those same resolutions all over again.

I hope you have a great 2026.

Thanks for reading this article, I really hope you enjoyed it. You can subscribe to my monthly newsletter below, find me in picture form on Instagram @johnjsills, or in work mode at The Foundation and LinkedIn.