You’re reading CX Stories, a newsletter about customer experience innovation. If you want to join the 4000+ lovely people who receive it every month, just enter your email address below.

Here’s an admission you won’t often hear from someone who works in Customer Experience. I really dislike the ‘let’s focus on the basics’ mentality.

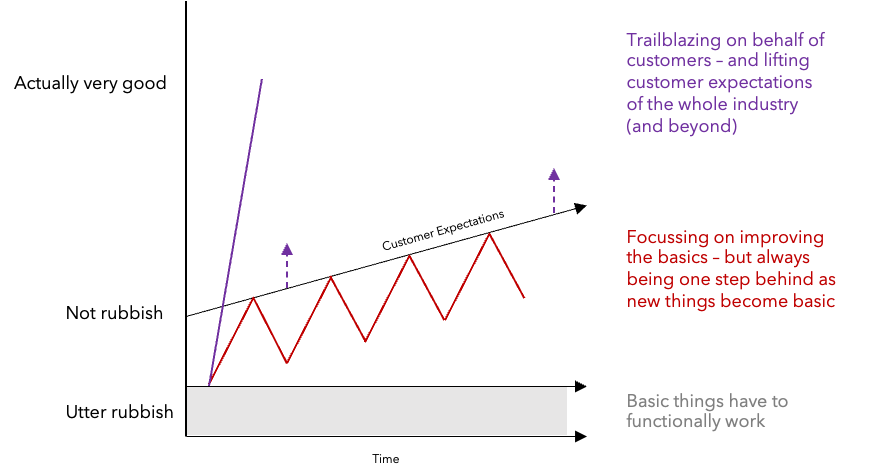

The same pattern is seen time and again across organisations. The first job is to ‘fix the basics’ (sometimes called the brilliant basics), prioritising effort based on what customers are complaining about the most.

But whilst that’s happening, those sneaky customers change their expectations, wowed by another company in another industry that’s found a new and better way to do something.

So, more basics appear that need putting right as customers complain about something that used to be acceptable. This creates a vicious cycle with the company always one step behind, unable to catch up with their customers, and unable to compete with their competitors.

They fall into the forgotten middle, slowly disappearing into irrelevance despite lots of effort to improve, a follower that’s the same as all the rest. Internally, the expense doesn’t seem to be worth the reward, causing senior leaders to lose faith in being customer-led.

Of course, it’s right to fix the stuff that’s genuinely broken: A payments system that doesn’t work; a contact centre that keeps you on hold for an hour; a Deliveroo driver that doesn’t deliver.

But outside of that, the trouble with only focussing on ‘the brilliant basics’ is that, well, it only ever gets you to the level of ‘not rubbish’. It gets you to parity – and no further.

I see this as part of a broader issue of organisations looking at customer experience in a reactive, negative way, as something to improve as opposed to something to excel at. (It’s interesting how senior management calls to people who have filled in an NPS survey are nearly always exclusively focussed on those who’ve had a bad experience, rather than also calling those who gave a 10 to say thank you).

The alternative is for companies to show real proactivity, not waiting for customers to tell them what they want, but to trailblaze on their behalf, taking their industry to new levels and creating an experience that customers didn’t know was possible – and thereby redefining what customers expect.

Is next-day delivery a basic, or a delighter now? Or free delivery, for that matter? When it launched (and was then popularised by Amazon), it was seen as a market-leading offer. Anything you want, almost when you want it.

The knock-on effect on competitors is huge. Suddenly, three- or four-day delivery – which would have been a wonderous thing a few years before – now seems like an age, almost something complaint worthy. And if you have to pay extra for it? Even worse!

A basic, reimagined as a way to delight customers, altering the whole industry forever.

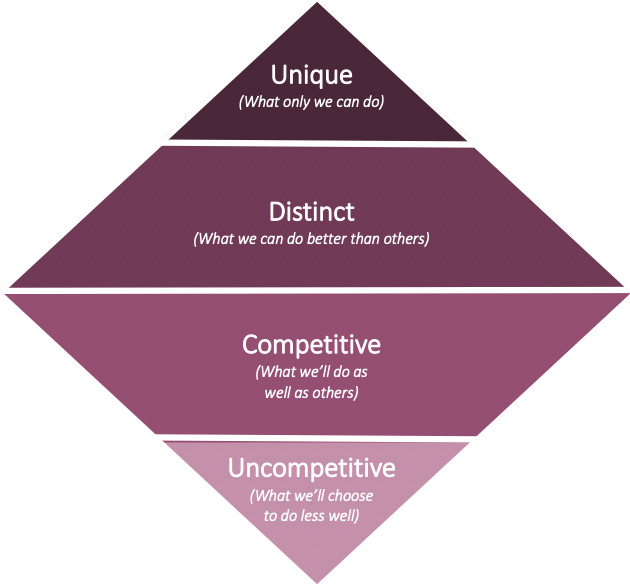

To do this, organisations need to deliberately split their time, absolutely fixing the stuff that’s broken and making some of the basics ‘good enough’, but also committing time to the stretchy, distinctive delighters. This means understanding the strengths they have to build on, where they can be unique and distinctive against their competitors and accepting the things they’re happy to be at parity (or even below) on. A Customer Experience version of Strengthsfinder, if you will.

As Rory Sutherland said in his recent article on the excellent Kano model, which promotes the importance of ‘Delight Qualities’:

‘These are often the most interesting because they deliver extraordinary gains in happiness at very little cost. Unfortunately, because they seem unquantifiable to the engineers or finance people making the decisions, they are often the first to be cut. The glass roof in the new London cabs is a delight quality: most of London’s architectural value is above eye level. Yet I cannot begin to imagine how many arguments the poor designer must have endured to get this enhancement into production. Steve Jobs understood this very well: notably the first iPhone didn’t do much, but it did it delightfully.

Or to put it another way

‘The people who built St Pancras station instinctively understood Kano theory; the people who built Euston didn’t.’

Thanks for reading this article, I really hope you enjoyed it. You can subscribe to my monthly newsletter below, and find me in tweet form @johnjsills, in picture form on Instagram @johnjsills, or in work mode at The Foundation or on LinkedIn.